Ken Burns and the Ali Documentary - Is Storytelling a Black and White Issue?

The controversy over the famed documentarian's work should lead to constructive dialogues about race and art.

The arts and entertainment arena is seeing its share of racially tinged controversies. Race and racism-related issues are never far removed from any aspect of society, but several recent topics have engendered particularly complex discussions about how race and history intersect.

Recently, the Woman King movie controversy saw some segments of Black society calling for a boycott of a movie that seemingly celebrates empowered Black women on the basis that it did not fully address the history of Africans enslaving other Africans.

Variety magazine is highlighting a controversy that happened last year but is important to discuss given the continual assessment and reassessment of how and in this case, who presents racially charged topics.

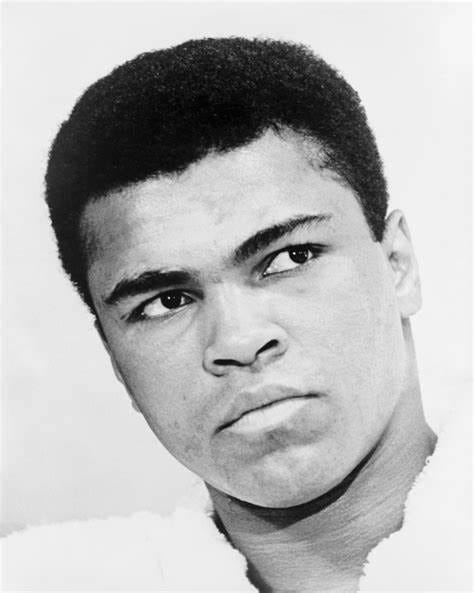

The magazine has published an article about the outrage in the Black community at the news that acclaimed documentarian Ken Burns was developing a project about the life of Muhammad Ali.

Burns, who is White and widely considered one of the best if not the best contemporary documentarian, was not considered an appropriate choice to helm the production by some because of his race.

In fact, 140 documentarians sent an open letter to PBS, who underwrote the documentary, expressing their displeasure about Burns’ involvement due to the fact that his work is usually seen as definitive and would preclude future, Black-led projects about the late heavyweight boxing champion.

The letter said:

“Your commitment to diversity at PBS is not borne out by the evidence. When you program a series on Muhammad Ali by Ken Burns, what opportunity is there for a series or even a one-off film to be told by a Black storyteller who may have a decidedly different view?”

Moreover, the Variety article quotes Black documentarian Stanley Nelson, who says

“I don’t think that Ken Burns can understand what Muhammad Ali, on a visceral level, meant to the Black community,” says Nelson. “Can he understand it on an intellectual level? Yes. But what I’m trying to do as a filmmaker is to translate to film what the Black community felt about a Black man like Muhammad Ali or Miles Davis, and if you cannot understand what the Black community felt on a visceral level, then you can’t put it into the film.”

Nelson went on to say that “anybody can make any film they want,” but said that White filmmakers are often given the opportunity to make art about Black people, but not the other way around.

Black Academy Award-winning director Roger Rees Williams agrees with his Blackness being able to inform Black stories, but disagrees that his color should limit what stories artists should be allowed to tell:

“If I tell a story about the African American experience, seeing it through my lens as an African American is going to be totally different than how a white person tells that story. It just is. But I make all kinds of films. I made “Life Animated,” and there wasn’t a Black person in that film. It was about a white, upper-middle-class family, and I can tell that story.”

For his part, Burns both acknowledges the need for more diverse storytellers, yet resists the notion that he is ill-equipped to tell non-White stories:

“I don’t accept the idea that only people of a particular background can tell certain stories about the past. One of my favorite quotes in the whole world is Martin Luther King’s: ‘All people are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.’ So, we all have to see the other and be seen by the other. For far too long, many people have not been seen or heard by the other. [But to say] ‘You are white, how could you possibly do it,’ that just violates everything Martin Luther King says. That’s a re-separation of people, which we don’t want.”

Obviously, this is an issue that will not be solved overnight. But there needs to be concrete solutions developed to address this issue, as well as a more wholistic view of art and artists.

We know that all diverse artists face built-in disadvantages. Most of their stories are not seen as important, and those that are seen as important, like that of Muhammad Ali, are usually told by Whites.

(Interestingly, there was no hue and cry from Black filmmakers when Burns filmed “Unforgiveable Blackness,” a documentary about Jack Johnson, the first Black heavyweight boxing champion. Is it because Johnson’s once celebrated and controversial and career life (in ways both similar and vastly different than Ali’s) is so far removed from recent history that it didn’t matter who told his story? If Stanley Nelson and those who agree with him are correct, shouldn’t Johnson’s story have been told by a Black filmmaker?)

Opportunity, funding, advertising and marketing are seemingly insurmountable hurdles for non-White filmmakers. No one can honestly argue differently.

Therefore, established, entrenched White filmmakers like Ken Burns should make every effort to identify, mentor, and empower filmmakers of color. Apprentice them. Encourage them. Teach them while at the same time learn from them. Work to get them funded and afforded the same opportunities as their White counterparts.

In addition, when White filmmakers want to make films involving non-White subject matter, they should invite the participation of Black historians and researchers who can offer their unique perspectives, providing balance, nuance, and dare we say color to their palettes.

Those who decry Ken Burns making an Ali documentary are right that his production may seem like the final word on the subject, but with a life as rich and complex as Ali’s, it doesn’t have to be that way.

Black documentarians could bring additional light and shading to their storytelling that may be beyond Burns’ considerable capabilities, or at the very least present different and intriguing angles that his work did not bring forth.

In the end, Stanley Nelson is correct when he says that “anybody can make any film they want.” Art is informed by the artist and is only as accurate and truthful as their scope, vision and outside influences allow.

When it comes to telling history, the story of a life, a life lived mostly in the public eye, and the life of one of the most famous people of any color to have ever lived, telling the whole story will always be a worthy, yet elusive challenge.

Ali’s life, like any historical figure, bears telling and retelling.

Whether it is a faithful retelling of history, poetic license, or a mixture of both is irrelevant.

Art is not history. It is a vision, a depiction, a rendering.

And it doesn’t care who tells it because art is never merely Black and White.