The aftermath of two racist incidents forty plus years apart demonstrate America’s infuriatingly inconsistent tenor.

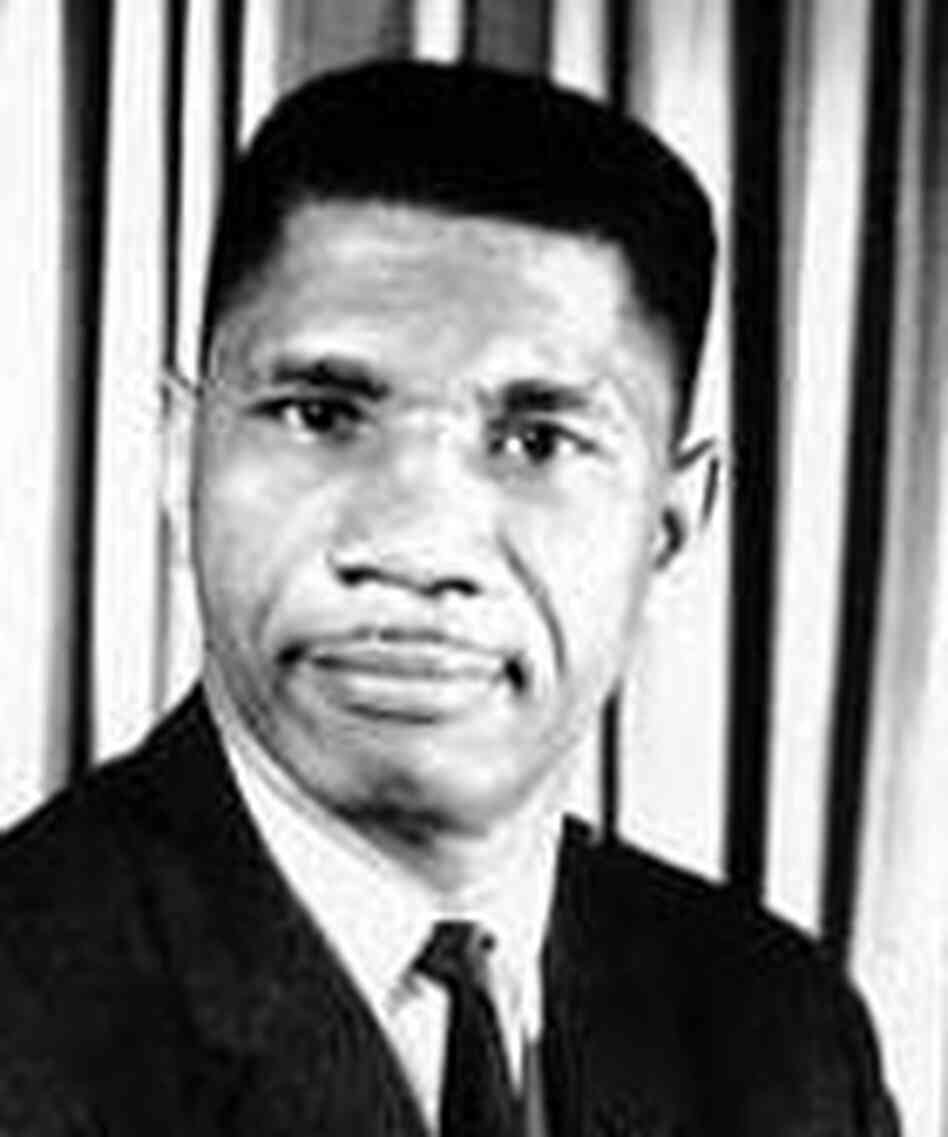

June 12th was the sixty-first anniversary of the assassination of Medgar Evers. Evers, the NAACP’s first field secretary in Mississippi, was shot dead in his driveway in 1963.

He survived combat against a foreign enemy in World War II only to die from homegrown White supremacy.

Returning from an early morning meeting with NAACP lawyers, Evers was shot in the back, the bullet piercing his heart. He was 37 years old.

Nine days later, Byron De La Beckwith, an avowed White Supremacist, was arrested for the murder. Two all-White juries deadlocked in 1964. De La Beckwith was literally judged by his peers since Jim Crow laws precluded Blacks from jury services.

Myrlie Evers, Medgar’s widow, did not give up seeking justice. She continued to press for a retrial, and in 1994, De La Beckwith was retried with new evidence, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison. He died in jail in 2001 at the age of eighty.

June 12th also marked a less satisfactory conclusion to another case of White Supremacy.

The Oklahoma Supreme Court dismissed a lawsuit by three survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre. The suit was seeking financial restitution from the City of Tulsa for the riotous loss of life and property that occurred during May 31-June 1, 1921 in the Black Tulsa enclave of Greenwood.

On those dates, a White mob, some of whom were deputized, looted and burned Greenwood, which had been known as Black Wall Street. As many as three hundred Black Tulsa residence were killed, and thousands were imprisoned in internment camps.

Of the three massacre survivors who filed suit, two women, both over one hundred years old, are still alive. The lone male survivor who filed suit died in 2022 at the age of 102.

The court ruled that while the plaintiff grievances were valid, the destruction of Greenwood did not fall within the state’s public nuisance statute.

The court said in its ruling:

“Plaintiffs do not point to any physical injury to property in Greenwood rendering it uninhabitable that could be resolved by way of injunction or other civil remedy. Today we hold that relief is not possible under any set of facts that could be established consistent with plaintiff’s allegations.”

The plaintiffs are considering filing an appeal so the Court will take another look at the case, but it is unlikely to result in a different outcome.

Herein lies the American contradiction.

In this country, justice is slow and unsure for Blacks, although in the Evers case, it eventually prevailed.

For the two Oklahoma women whose relatives and friends were beaten, murdered, and burned out of their homes and businesses, justice hasn’t prevailed, and likely never will.

The Oklahoma court could not find “physical injury to property rendering it uninhabitable that could be resolved by way of injunction or other civil remedy,” even though the National Guard had to come in to restore order, thirty-five square blocks of Greenwood were destroyed, and there was demonstrable loss of life.

No one can convince me that a White Tulsa neighborhood would have received the same ruling. The residence would have received speedy reparations.

This is why Black people have a love/hate relationship with America, one which leans more towards hate than love.

We love America for its potential, and the beauty on display on the rare occasions when potential blossoms into reality.

We hate America because most often its potential is unrealized.

Our American experience will give us a warm hug and follow it with a kick to the teeth.

The fantasy America found in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution is beautiful, but the reality is that America has leprosy.

It is rotten and diseased to the core.

And the ugliest part is its treatment of non-Whites.